We Are Made By History: The History of Money in America

In the hit musical Cabaret, Liza Minnelli sang about how “Money Makes the World Go Around,” but how much do you really know about the currency we use every day? Our national currency has a long and very detailed history. While we often take our “tap to pay” lifestyle for granted, we sometimes forget about the history that got us to this point. If you think that the bags full of coins that we remember from the cartoons of our childhood is something that only existed in “Toon Town,” it’s time for your history lesson. So, if you have ever been curious about those “Greenbacks” burning a hole in your pocket, read on to learn a little more about the history of money in America.

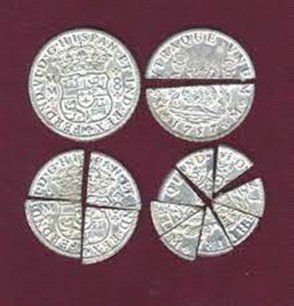

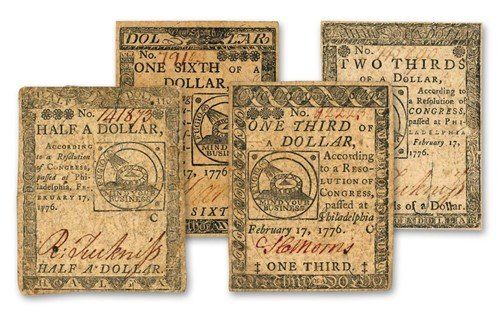

- Colonial period: This was a time of great inconsistency for currency as the nation began to take shape. During this time, a wide variety of coinage was found in circulation ranging from British pounds to German thalers to Spanish milled dollars and even some coins produced by the colonies, themselves. The most coveted became the Spanish milled dollar due to the silver content. Can you imagine that, when change was due for a purchase, the coins were often cut into halves, quarters, eighths and even as small as sixteenths?

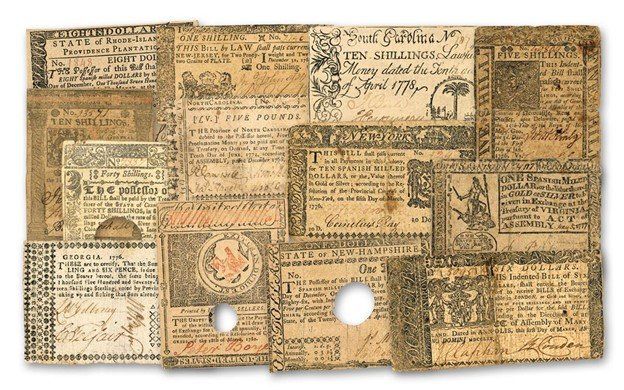

- 1690: Colonial notes were the first recognized form of paper currency in the United States, and Massachusetts was the first colony to issue its own paper money to fund military expeditions with other colonies quickly following suit. This, however, created some tensions between the colonies and Great Britain which resulted in the Currency Acts of 1751 and 1764 designed to curtail those bills’ designation as legal tender.

- 1775: At the height of events leading up to the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress issued the first overarching colonial currency, known as Continentals. While the bills differed greatly from the ones that we know today, they did carry with them a few familiar motifs that we still see on our notes today – including the unfinished pyramid. These bills were also designed to specifically address a very specific problem of the day – economic warfare in the form of counterfeiting by the British. To combat this issue, Benjamin Franklin’s printing firm added several unique designs such as nature prints to the notes that made them more difficult to duplicate

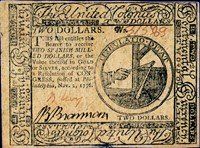

- 1776: On June 25, 1776, nine days prior to the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress authorized the issuance of a new $2 denomination referred to as “bills of credit” for the defense of America.

- 1785: Evolved from the Spanish-American figure for pesos, the “$” is adopted.

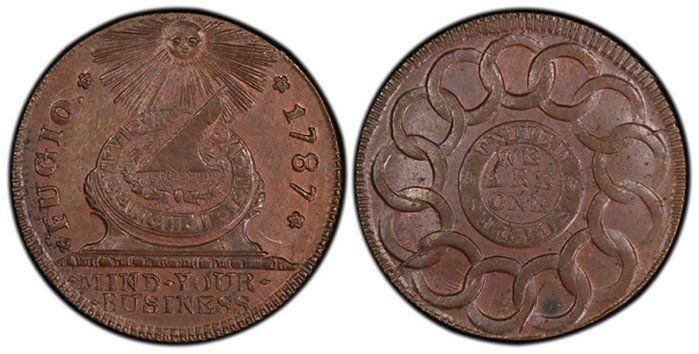

- 1787: Congress authorized the production of copper cents, also known as Fugio cents. These coins featured a sundial on one side and a chain of 13 links on the other. However, after the ratification of the Constitution the following year, a new government was established and a new debate over national coinage created.

• 1789: The U.S. Treasury was established on September 2, 1789.

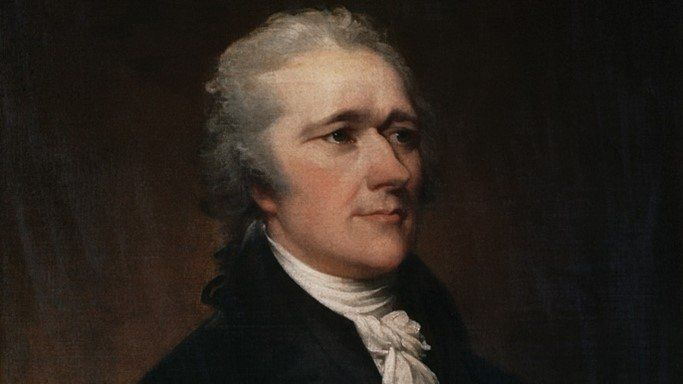

• 1791: The Bank of the United States was established by Alexander Hamilton to create a system of credit for the government. This was the first of several U.S. banks to issue private currencies to facilitate the acts of borrowing and lending. As many Americans were uncomfortable with the idea of a large, powerful bank and, therefore, opposed the concept, when the bank’s 20-year charter expired in 1811, Congress failed to renew it by one vote.

- 1792: Due to runaway inflation and the collapse in value of the continental currency, the Coinage Act of 1792 was passed, and the first national mint was opened. As previously mentioned, the Spanish milled dollar was the preferred currency of the Colonial period, so this became the model for the new national currency. The design of the first coins released (pictured below) were wildly unpopular due to the “frightened” portrayal of Lady Liberty and the chain links which many associated with oppression. The design was quickly revised to a more pleasing image of Lady Liberty and the chain replaced with a wreath. While great in theory, the Mint struggled with supply and demand issues for many years until the production finally grew to mee the demands of the growing nation. Legislation temporarily allowed certain foreign coins to continue to circulate until the Mint was able to meet the country’s demands. This remained until the Coinage Act of 1857. The Act also disallowed states to issue paper currency, a role that was now replaced by private entities and banks issuing thousands of different notes of tender. This process lasted for nearly 70 years before the federal government, once again, began to issue its own paper currency. The Coinage Act of 1792 specified that all coins were to feature an “impression emblematic of liberty,” the inscription “LIBERTY” and the year of coinage. All gold and silver coins were required to feature an eagle and the inscription “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.”

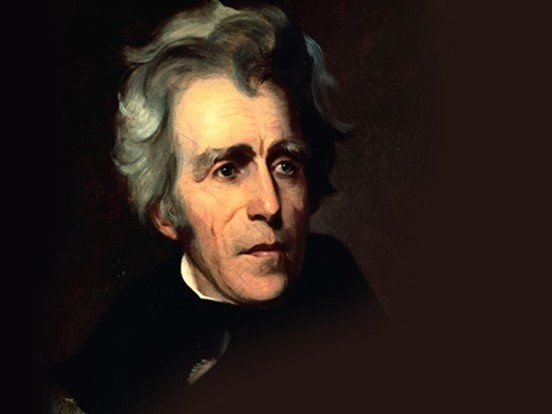

- 1816: History repeated itself. By 1816, there was a shift in the political climate that, once again, favored the idea of a central bank, albeit by a narrow margin, and Congress opened the Second Bank of the United States. This was quickly met by opposition from Andrew Jackson, a foe to the central banking system, who was elected President in 1828. He rallied support for his attack on banker-controlled power from Americans so when the Second Bank’s charter expired in 1836, it met the same fate as the first one.

- 1836-1865: This became a confusing time for monetary transactions as state-chartered banks and unchartered “free banks” began issuing their own notes which could be redeemed in gold. These banks also began to offer demand deposits to enhance their role in commerce. This led to a rise in volume for check transactions and the creation of the New York Clearinghouse Association in 1853, allowing the city’s banks to exchange checks and settle accounts.

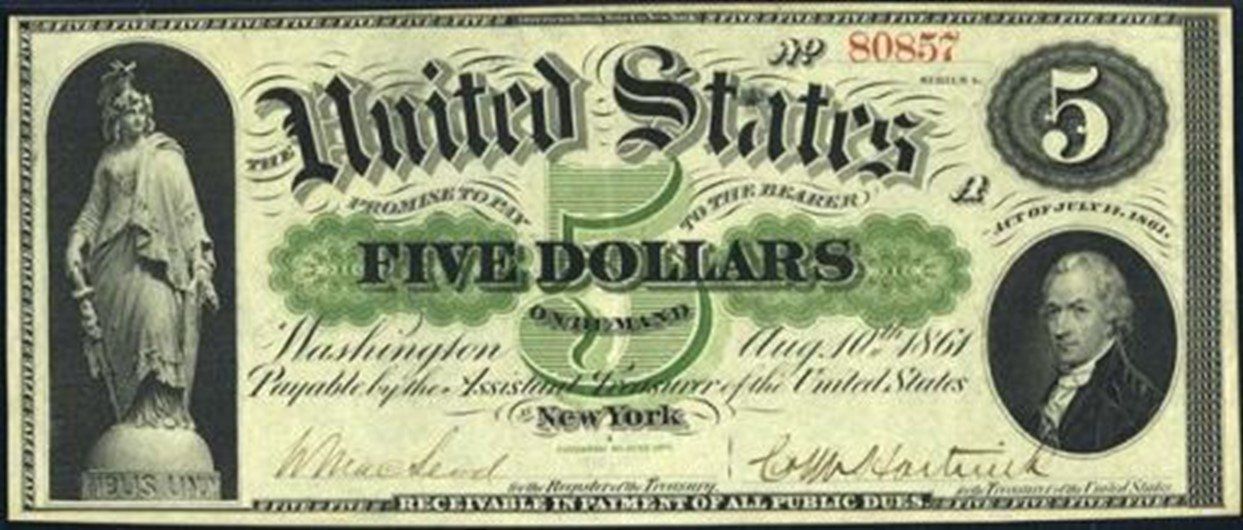

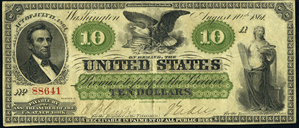

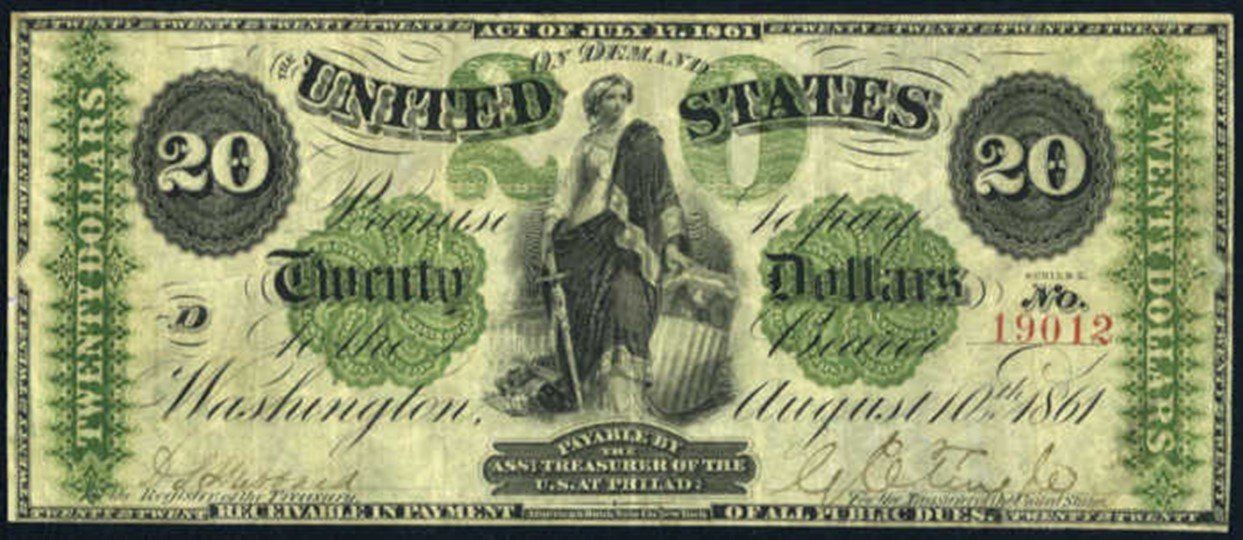

- 1861: Needing to finance the Civil War, Congress authorized demand notes to be issued in denominations of $5, $10, and $20, so named because they were redeemable “on demand” in coin. Utilizing an innovative chemical ink which gave it a unique green color to guard against the new technology of photographic copying, the notes were nicknamed “Greenbacks.” Images on the Union notes included such portraits as Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln

- 1861: The Confederacy began issuing its own paper currency, nicknamed “greybacks,” also named for their ink color scheme. These notes featured such images as slaves working in fields (on the $100 note,) as well as portraits of figures such as Andrew Jackson, John C. Calhoun, Jefferson Davis, Lucy Holcombe Pickens and George Washington.

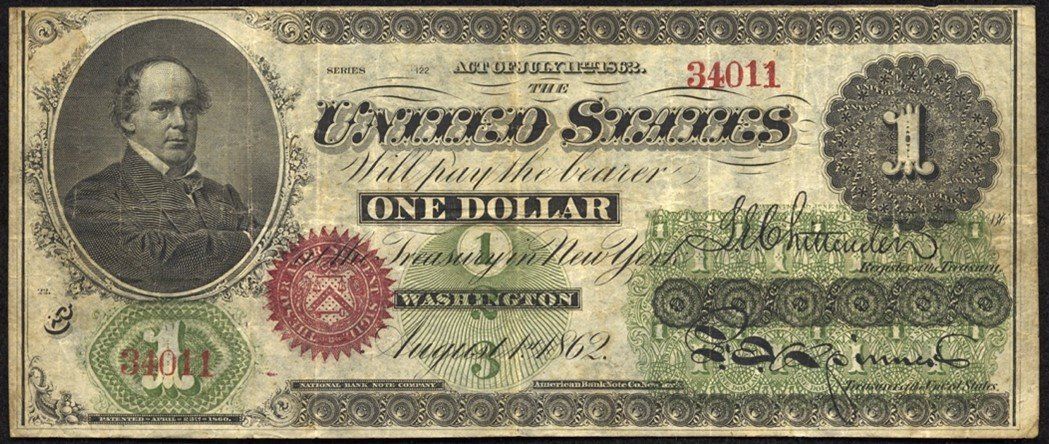

- 1862: The first $1 Legal Tender Note is issued featuring a portrait of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase.

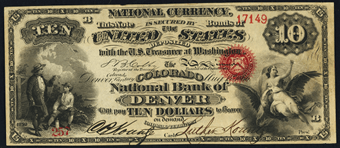

- 1863: A national banking system and uniform national currency were established under The National Banking Act of 1863. Under this Act, banks were required to purchase U.S. government securities as backing for their National Bank Notes – the most widely accepted currency circulating between the Civil War and World War I, being issued from 1863 through 1932. National Bank Notes were printed by private bank note companies as contractors to the Federal government from 1863 until 1877, at which time the Federal government took over the printing process.

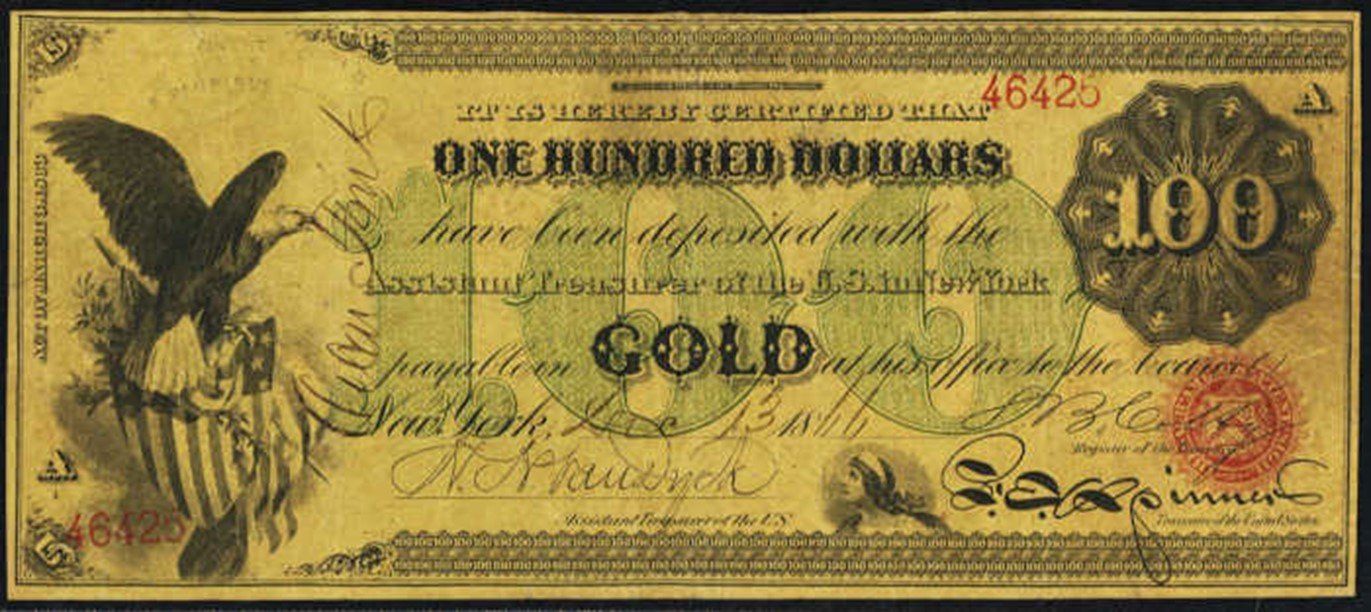

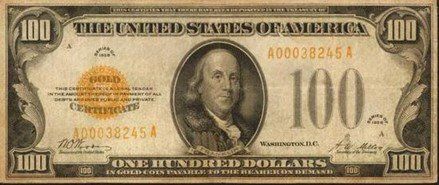

- 1863: Gold certificates were first issued in the United States in 1863, however, were not put into general circulation until 1865, and remained in use until 1934 when all gold certificates were called in from the Federal Reserve Banks because of the Great Depression having resulted in runs on the banks and demands by the public for gold. From 1934 until 1974, it was illegal for U.S. Citizens to hold gold bullion or certificates. The look of the gold certificate changed many times over the course of its lifetime. Below are examples from 1863 and 1928.

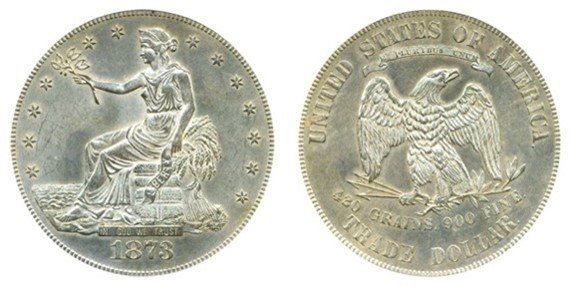

- 1873: The United States began to mint trade dollars. As global trade began to increase, particularly between the US and China, the United States faced a new challenge. Their new trade partner favored payment in the Mexican peso over the US dollar due to the content of pure silver contained in the coinage. This caused US businesses to need to exchange their dollars for pesos to conduct trade, resulting in costly broker fees. The federal government answered back with the trade dollar. These trade dollars weighed in slightly heavier than the peso and contained 90% silver, easing the country’s trade issues. However, this created a new issue. With the need for trade dollars, western mines began producing such enormous amounts of silver that the price of silver plummeted, eventually resulting in a halt in production ordered by then Treasury Secretary John Sherman two years later. The Treasury continued to issue proof strikes through the1880s with 1884 and 1885 being the most rare.

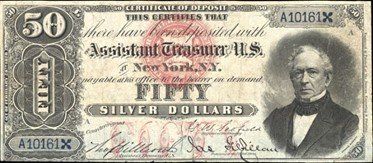

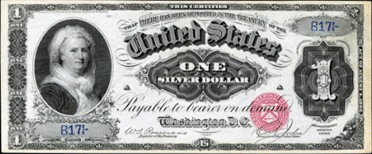

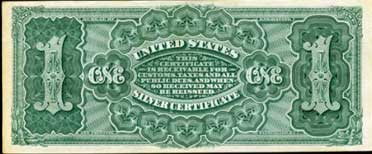

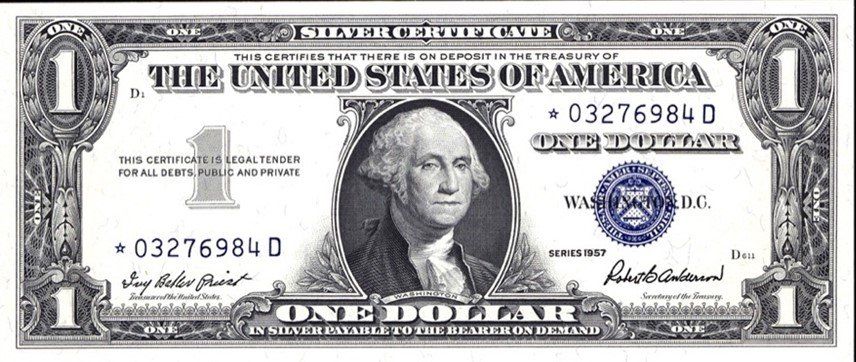

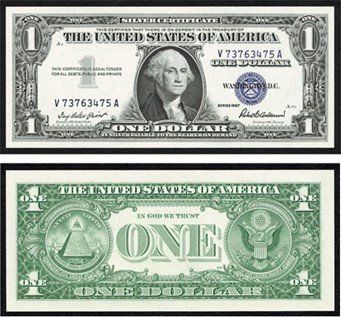

- 1878: Congress directed the production of five different issues of silver certificates, including the first and only U.S. banknote to feature a woman on the front – Martha Washington. These bills were backed by actual silver and were first issued in exchange for silver dollars in 1878. These remained in circulation until the early 1960s when rising silver prices threatened to undermine this system of currency, at which time Congress eliminated the silver certificates as well as the use of silver in circulating coinage. Much like its predecessor, the gold certificate, the silver certificate also changed its look many times while in circulation. Below are examples of a $50 silver certificate from 1878, a $1 silver certificate from 1886 and a $1 silver certificate from 1957.

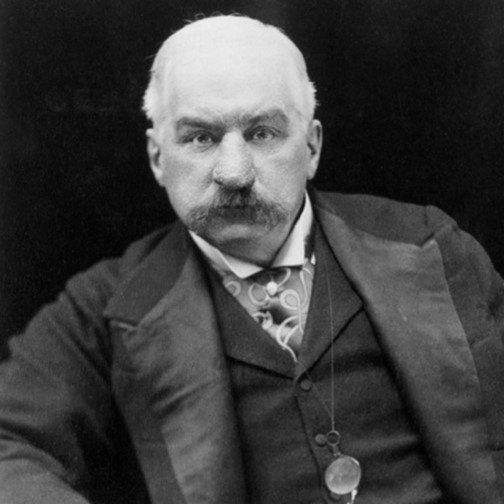

- 1893: Despite the National Banking Act of 1863 adding some measure of stability to the currency issues plaguing the young nation, it was becoming increasingly clear to the public that the nation’s financial system was in need of serious attention. Financial panic and bank runs became the norm of the day until 1893 when a banking panic triggered the worst depression the United States had seen to that point. It was only after the intervention of financial mogul J.P. Morgan that the economy stabilized.

- 1907: After Wall Street speculation results in failure leading to a particularly sever wave of banking panic, J.P. Morgan is once again called upon to avert monetary disaster. While opinions over the solution remained deeply divided, by this time, most Americans were demanding reform of the banking system.

- 1908: The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908 is passed as an immediate governmental response to the banking crisis of 1907. The Act allowed for emergency issuance of currency during times of financial crises. The Act also created the national Monetary Commission to search for a long-term solution to the nation’s banking and financial system issues.

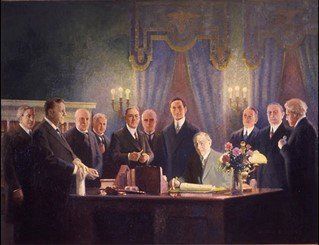

- 1912: Woodrow Wilson sought the advice of Virginia Representative Carter Glass and H. Parker Willis, a former professor of economics at Washington and Lee University, to formulate a solution to the U.S. financial issues. Carter Glass would soon become the chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Finance. By year end, Glass and Willis presented Wilson with a proposal that would eventually become, after some modifications, the Federal Reserve Act.

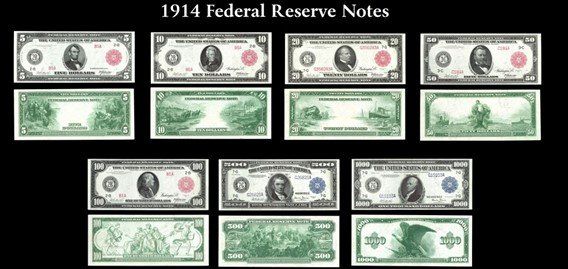

- 1913: After a year of contentious debate, on December 23, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law, creating a “decentralized central bank,” balancing the competing interests of private banks and popular sentiment. Additionally, the Federal Reserve Act created the surviving modern form of currency by giving the federal government the authority to issue Federal Reserve Notes (U.S. dollars) as legal tender. By this time, most of the design elements that we continue to see in circulation today were already determined by the dollar’s predecessors before the Federal Reserve Note was born. Many of these early notes featured presidents on the front, while the back pictured iconic Americana, such as the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock.

- 1933: In the aftermath of the Great Depression, Congress passed the Banking Act of 1933, better known as the Glass-Steagall Act. This required the separation of commercial and investment banking, as well as the use of government securities as collateral for Federal Reserve notes. Among other things, the Act also created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and outlined additional criteria for bank oversight by the Fed to help protect the end consumer. As part of the reforms, President Roosevelt also recalled all outstanding gold and silver certificates, effectively putting an end to the gold standard.

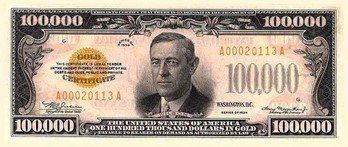

- 1934: While never circulated or issued for public use, in 1934, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing created the $100,000 gold certificate note for the purpose of conducting official transactions between Federal Reserve banks. A total of 42,000 of these bills were printed. While it is not legal for collectors to hold the $100,000 bill, some institutions such as the Museum of American Finance display them for educational purposes. The Smithsonian Museum and some branches of the Federal Reserve System maintain some of these rare bills in their possession, as well.

- 1935: The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is created as a separate legal entity by the Banking Act of 1935. The Act also removed the Treasury Secretary and Comptroller of the Currency from the Fed’s governing board and set the member’s terms at 14 years.

- 1957: The $1 bill became the first U.S. currency to feature the motto “IN GOD WE TRUST.”

- 1963: The $1 bill began replacing the $1 Silver Certificate. The new bills featured a new border design on the front and the serial number and treasury seal printed in green ink.

- 1969: The $1 bill replaced the wording of the treasury seal with English as opposed to the original Latin.

- 1978: The Humphrey-Hawkins Act required the Fed chairman to report to Congress semi-annually on monetary policy goals and objectives.

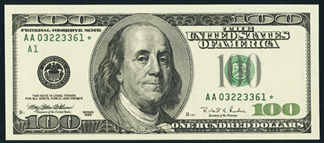

- 1996: March 25, 1996 brought us the most significant design change to United States currency since 1929 in the form of the $100 bill with new anti-counterfeiting technology. The new enhanced security features included optically variable ink that changes from green to black when viewed from different angles, a watermark of Benjamin Franklin and the reverse image of Independence Hall. One of the most instantly recognizable changes on the 1996 series $100 bill is a significantly larger and higher-quality portrait of Benjamin Franklin.

- 1999: The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act was passed, effectively, overturning some nuances of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 by allowing banks to offer a menu of financial services, including investment banking and insurance.

- 2003: Beginning with the $20 bill, more colors were added to the bills in addition to more advanced anti-counterfeiting technology.

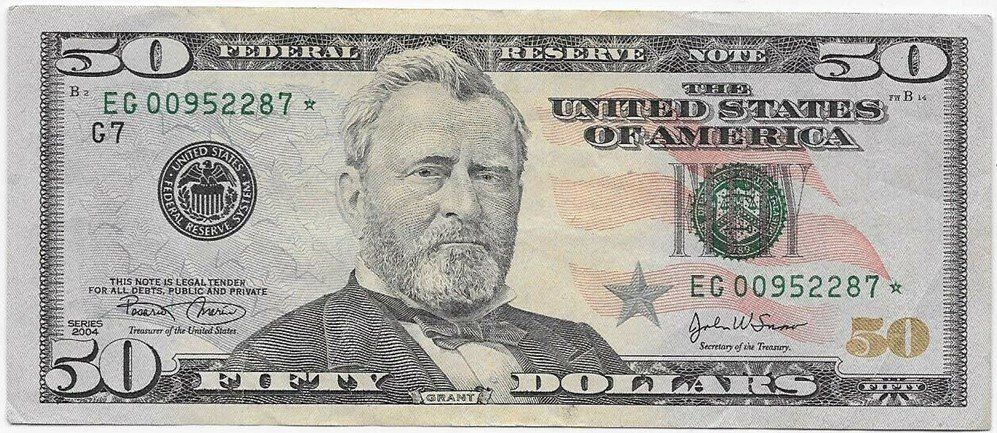

- 2004: The next bill in line to see the enhanced security changes was the $50 note, issued under Series 2004, beginning September 28, 2004. The revisions to the $50 bill brought us the first use of multiple colors on U.S. Currency sine the Series 1905 $20 Gold Certificate. The vibrant design included the addition of a red and blue colored image of an American flag background.

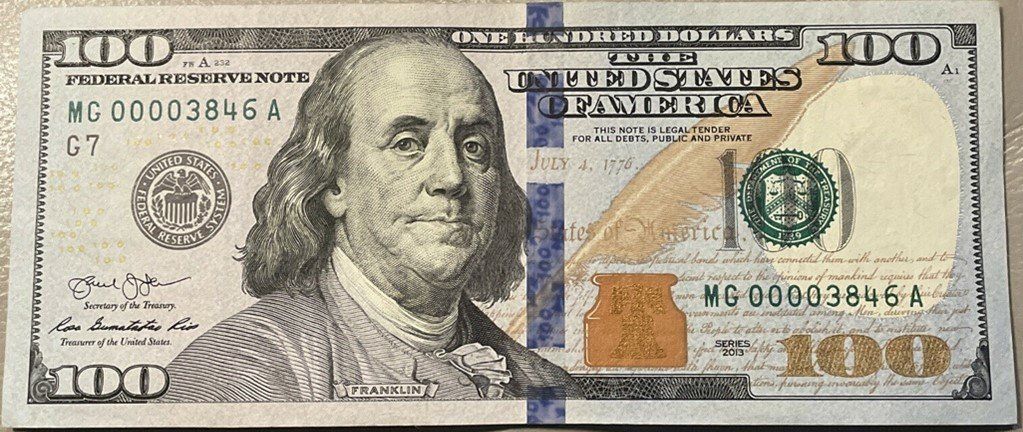

- 2013: October 2013 was the first appearance of changes to the $100 bill that had been approved three years earlier in April of 2010. The revisions made to this series of the $100 bill included the addition of a brown quill to represent the one used to sign the Declaration of Independence and the image of an inkwell that appears when viewed from different angles. Additionally, the image of Benjamin Franklin was retooled and is no longer within the traditional border. A teal background was added to give the bill additional color as well as coordinate with a 3-D security ribbon that contains miniature images of the Liberty Bell that change to the numerals “100” as the bill is viewed at different angles.

Throughout our nation’s history, our currency has gone through nearly as many changes as our country itself. We can only expect that additional changes will continue to come as technology continues to advance and our history continues to progress. Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “We are not makers of history. We are made by history.” Every piece of history, no matter how seemingly insignificant has helped to shape the landscape of the country we call home and how we do business today.

If you need help turning your financial history into your financial future, contact our advisory team where Sound Wealth Management is more than just our name.